COUNTING BUDDHISTS

Introduction

An online search for the number of Buddhists in the world today returns results ranging from 400 million to 1.6 billion people. How can there be such a wide range of answers, and how can we adequately evaluate the missional challenge and the advance of the gospel if we can’t even figure out how many Buddhists there are?

There are two major factors that affect how Buddhists are counted. The first is how to count Buddhists in China. If the population of China is counted as atheist, which is the position of the Chinese government, then the number of Buddhists worldwide would be closer to the lower end of the estimates. On the other hand, if the Chinese population is considered Buddhist (at least in worldview), then the higher end of the estimates would be more likely.

The second major factor in counting Buddhists accurately is determining how to define what a Buddhist is. Unlike most religions that focus on right beliefs (orthodoxy), Buddhism focuses more on right practices (orthopraxy). Typically, when trying to determine the number of adherents to a particular religion the focus is on whether or not a person holds a particular set of beliefs. However, when considering a religion that emphasizes right practice over right belief, it is probably more accurate to look at what people do rather than what they believe.

Four Types of Buddhists

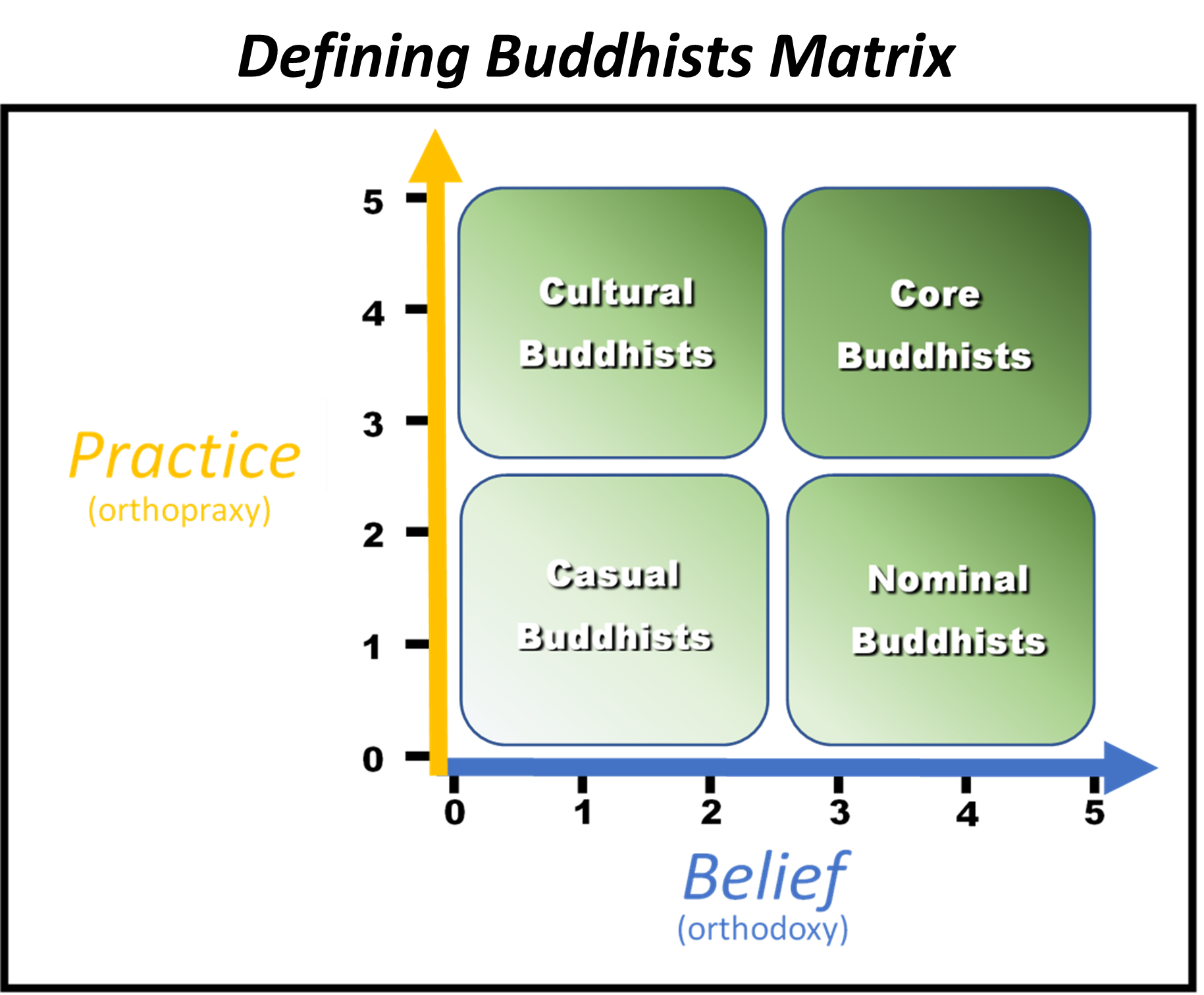

Change The Map (CTM) has developed a matrix that helps define what a Buddhist adherent is, and thus how to count them. It is not a precise measurement but provides categories in which to place Buddhists, from those who are extremely nominal to those who are extremely devoted. Considering the various combinations of a person’s commitment to Buddhist beliefs and practices, we can place them into the following four general Buddhist adherent types:

Core Buddhists – high belief / high practice:

Core Buddhists have both a high level of belief and a high level of practice. These adherents include monks, nuns, and actively engaged laypeople who form the core of Buddhist communities.

Nominal Buddhists — High belief / low practice:

Nominal Buddhists would likely self-identify as Buddhist and affirm belief in Buddhist teachings, but fail to engage in day-to-day observance and practice. For example, this group would include those who agree to the Five Precepts (see The Five Precepts right), yet continue to regularly drink alcohol, eat meat, etc.

Cultural Buddhists – low belief / high practice:

Cultural Buddhists are those who grew up in a Buddhist culture and follow most Buddhist practices despite not believing in the teachings of Buddhism. This includes young people who attend various Buddhist festivals and regularly participate in giving offerings to monks, not because they believe it, but because that is what their family and neighbors have always done.

Casual Buddhists – low belief / low practice:

Casual Buddhists have both low belief and low practice. They likely do not self-identify as Buddhist, but have nonetheless incorporated Buddhist elements into their regular life. This may include those who suppose karma may be a valid law of the universe or those who practice yoga or mindfulness meditation but either downplay the Buddhist aspects of these beliefs or practices or are ignorant of them. This low-commitment participation is analogous to a non-Christian college student regularly attending Chi Alpha or Cru (formerly Campus Crusade for Christ) events just for fellowship and fun.

Using the Defining Buddhists Matrix

To use the Defining Buddhists Matrix first determine the number of the above practices engaged in and mark the corresponding number on the vertical “Practice” axis. Next, determine the number of the above beliefs embraced and mark the corresponding number on the horizontal “Belief” axis. Look at where the indicated practice and belief numbers intersect to identify the type of Buddhist.

CTM has adopted a “rule of two” in interpreting Defining Buddhists Matrix results. There must be a minimum of two identifying Buddhist factors present in order to qualify as an adherent. For example, if a person scores one on the belief scale and zero on the practice scale, they are not counted as a Buddhist adherent. The same goes for a person who scores zero on belief and one on practice. A person who scores two on the practice scale and zero on the belief scale would be counted as a “casual Buddhist.” Likewise, a person who scores one on each scale would be counted as a “casual Buddhist.”

Practices (orthopraxy)

The five Buddhist practices listed can be seen around the world among Buddhists of various commitment levels. These practices can shift attitudes and beliefs over time to align with Buddhist beliefs. Often Buddhist teaching is incorporated into these practices and sometimes Buddhist terms are changed that may obscure the Buddhist origin of the practice. For example, mindfulness meditation teachings in a Buddhist setting focus on eliminating suffering but are sometimes re-branded as focusing on eliminating stress. These five practices are further explained below.

Practice Buddhist meditation

This includes any type of meditation derived from Buddhist meditation techniques. Mindfulness meditation is the most common type, but other forms are also used. Meditation is a key part of Buddhist practice intended to empty a person or detach them from people and the world around them to conform their worldview and values to a Buddhist worldview.

Practice regular Eastern religion-based physical practices

This includes yoga, tai chi, and some forms of martial arts. These types of practice are designed to be physical, mental, and spiritual, and intended to open a person to spiritual forces. Many of these forms of exercise predate Buddhism, but have been incorporated into Buddhist practice (i.e., yoga).

Visit Buddhist locations or events

This includes visits to Buddhist retreat centers, temples, monasteries, celebrations, etc. These visits may include formal events and instruction (such as participation in group meditation classes or annual retreats) or informal attendance at holiday celebrations that incorporate some religious element (such as attending new year celebrations that include burning incense for luck in the new year).

Use Buddhist icons or images for luck or protection

This category varies by culture and type of Buddhism, and can include prayer wheels, incense, charms, statues, protective tattoos, family altars, ancestor shrines, and cloths printed with chants that have been blessed by monks.

Do good works to make up for or offset bad works

Associated with the belief in karma is the practice of earning merit. The practice of doing good works to make up for or offset some bad works is a way that Buddhists try to earn enlightenment (or salvation) and is a key element of Buddhist practice. Doing good works could include formal Buddhist merit-making practices (such as giving gifts to a monk, donating money to a temple, reciting prayers, or ringing temple bells) or informal, habitual efforts to do good things to other beings (such as giving money to beggars, donating money to a local school, or feeding stray dogs).

Beliefs (orthodoxy)

The five beliefs used in the Defining Buddhists Matrix are key to identifying a Buddhist worldview. Full understanding of a particular belief is not necessary for it to be counted (i.e., a person may be counted as believing in rebirth, but does not need to fully understand the various realms and levels within Buddhist cosmology). These five beliefs are further explained below.

The Three Jewels

The Three Jewels are the Buddha (including Gautama Buddha, various other buddhas, and bodhisattvas), the Dharma (Buddhist teachings, including the various Buddhist scriptures), and the Sangha (community of monks and the Buddhist monastic system). Respect for the Three Jewels can range from somewhat informal respect of one of the three (e.g., recognizing the Dalai Lama as a great spiritual teacher constitutes respect for Buddha) to formally “taking refuge in the Three Jewels.”

Karma

Karma is a force or natural law that determines a person’s status or quality of life based on intentional behaviors in their past lives. Good deeds produce a good future and bad deeds produce a bad future. Upon death, if a person’s good deeds exceed his or her bad deeds, one will attain a higher existence in the next life.

God rejected or ignored, spirits feared

A personal, transcendent God of creation is rejected in Buddhism, yet various supernatural spiritual forces, including gods, are acknowledged. Various natural and ancestral spirits and ghosts potentially impact a person’s daily life.

Rebirth

Upon death, if one has not attained “enlightenment,” one will be reborn in a level of existence determined by his or her karma. The level of rebirth may occur in various realms, ranging from hell to heaven. Most Buddhists believe that countless rebirths are necessary to attain “enlightenment.”

Enlightenment

Often referred to as nirvana, enlightenment is the ultimate goal of Buddhism. It involves escaping the ignorance and suffering of existence and encompasses perfect peace and release from samsara, or the continuous wheel of birth, life, death, and rebirth.